After measuring the scores of nearly 400,000 people on the Sea Hero Quest game, an international research group has determined that people who grew up in urban environments have poorer spatial orientation than those who spent their childhood in the countryside. The data collected could help in the screening and treatment of neurological diseases that affect this ability, such as Alzheimer’s or dementia.

TDB keeps you informed. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram

Diego Salvadores 30/3/2022 17:00 CEST

The urban design of the place where we grow up influences cognitive processes during adulthood.

People who have grown up in a rural or suburban environment have a greater spatial orientation than those who have grown up in cities, especially those that follow an orthogonal layout, i.e. where straight lines predominate in the layout of streets. This is the finding of a study led by Hugo Spiers, a researcher at University College London (UCL) in the UK.

The study measured the degree of spatial orientation by analysing the patterns and scores obtained in the mobile game Sea Hero Quest from a sample of 397,162 people from 38 different countries.

The recreation is part of a citizen science initiative on neuroscience research developed by Deutsche Telekom, in collaboration with Alzheimer’s Research UK, video game developer Glitchers and several European universities.

The influence of urban topography

“Our ability to orient ourselves spatially in adulthood is largely explained by the topography of the place where we grew up. Thus, people who grew up in a city with a complex urban layout, such as Paris, have a better sense of orientation than those who grew up in an orthogonal city, such as Chicago,” Antoine Coutrot, a researcher at the French CNRS and co-author of the study, told SINC.

The test subjects performed a series of orientation tasks while playing the Sea Hero Quest game.

Previous research has shown that individual life experience is capable of shaping brain structure and function. Now, this study reinforces that idea by showing that the urban design of the place where we grow up influences cognitive processes during adulthood.

The subjects performed a series of orientation tasks, such as navigating a boat and locating certain control points shown on a map. After narrowing down the variables that could affect the outcome (age, gender, educational level, etc.), the experts found that the place where people had grown up influenced their performance in the game, while their current place of residence did not affect the final scores.

Spatial orientation is being lost

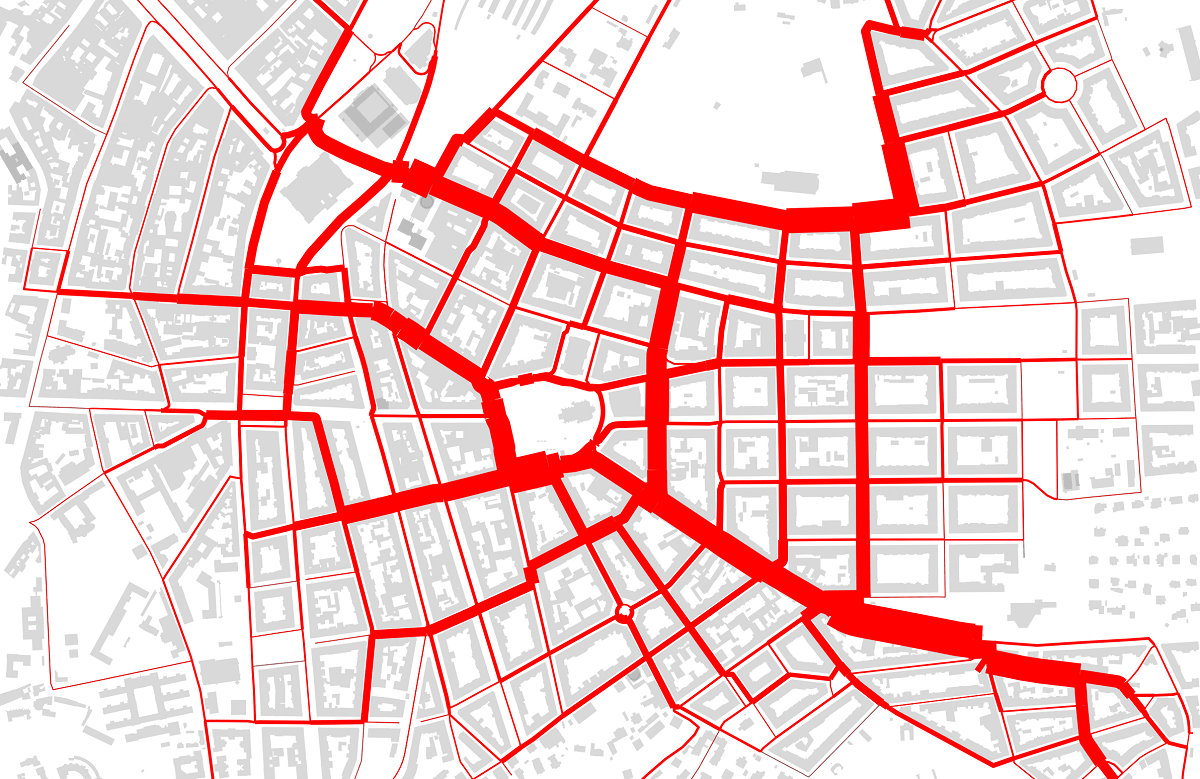

The researchers compared the study participants’ home cities by analysing the entropy (disorder) of the street networks, to measure the complexity and randomness of the layouts.

The researchers compared the clutter of the participants’ cities with their scores on the game.

People whose home cities had lower entropy i.e. ordered layouts such as Chicago or New York, scored worse on the orientation exercise.

In contrast, people in cities with more complex layouts, such as Prague, scored only slightly worse than those in rural areas.

The ability to orient in space also declines with age. “Subjects who grew up in areas with gridded streets oriented themselves comparably to people in rural areas five years older. In some areas, the difference was even greater,” explains Spiers.

Multiple therapeutic approaches

The Sea Hero Quest project was designed to aid research into Alzheimer’s, a neurological disease whose symptomatology in the early stages includes a deficit in the ability to orientate. “The data collected with Sea Hero Quest can be used as a benchmark to help identify people at risk of developing it.

“Our method offers the opportunity to study how thousands of people from different countries and cultures orient themselves in space and helps to shed light on how we use our brains in this regard. It may also help in the development of future diagnostics and treatments,” adds the researcher.

The data collected with Sea Hero Quest can be used as a benchmark to help identify people at risk of developing Alzheimer’s.

The vast amount of data collected by the initiative’s promoters can be analysed from different approaches. Current lines of research include establishing a link between sleep duration and quality and spatial location, while other groups “are focusing on diseases such as post-traumatic stress disorder, schizophrenia or certain brain lesions that affect a spatial orientation,” says Coutrot.

“These teams can analyse the spatial behaviour of their patients when they play Sea Hero Quest and compare it to our large dataset collected from the general population,” he concludes.